You are reading Halloween Heart, a subsection of Kaia Preus’s newsletter With Love From My Kitchen Table.

There are 206 bones in the adult human skeleton. I’ve had to memorize the names and places of most of these bones twice––first in my tenth grade biology class and second in the human biology course I took during college to fulfill a general education requirement. I liked memorizing the names of bones, pointing to their whereabouts beneath my own skin as I studied. The names were interesting and I could link them together using mnemonic devices and little stories I made up about the skeleton.

One day, I was in the science lab with two friends from class and our professor. We were practicing the names of the bones and muscles, and our professor wheeled over one of two life-size skeletons that were in the room for us to learn from. He pointed to bones and we raced each other to call out the correct term. He showed us how to tell that this skeleton was female by the size and shape of the pelvis.

After studying, we were packing up our notebooks when I turned to my professor. “That skeleton is really small,” I commented. The skeleton was much tinier than the other skeleton in the classroom, or that of other replicas, or even plastic Halloween decorations I’d seen for sale.

“Well,” he said, “it’s real.” A look came across his face––part apologetic, part fascinated. “She probably came from India or China.”

“How did she get here?” I asked. I was shocked. I was also horrified. I was also so, so curious.

“I don’t know exactly,” he said. “She might have been donated.”

I looked at the skeleton, her differences from the replica across the room crystallizing. She was under five feet tall whereas the replica skeleton was closer to six feet. The coloring of her bones was different, too––they looked as though they’d been dipped in tea and set out in the sun to dry. The replica’s bones were white, though its brightness was scuffed a bit by the fingerprints of studying students.

My professor wheeled her back to her place by the fake. She was facing the row of windows that looked out on our campus on a small hill in southern Minnesota. Students scurried past the windows, hurrying to classes and clubs and hang out sessions. When was the last time this skeleton––this person––walked quickly to catch a bus or train? Rushed to scoop up a crying child who had fallen and scraped a knee? Ran to jump in the arms of someone she hadn’t seen for a long time? How could she ever have imagined that after she died, she would end up here? In an air-conditioned science lab in a private liberal arts college in rural Minnesota with students reaching out their flesh and skin-covered fingers, pointing at and naming her naked bones: ulna, radius, meta-carpals?

As shocked as I was, I’ve found that having a real skeleton in a classroom is actually not an anomaly. Medical schools and universities around the world, but particularly in Europe and the United States, have been importing human skeletons for academic use for centuries. Most of these skeletons came from India, where, with a population of over one billion people, thousands of unclaimed bodies are found every year.1 People in the bone trade discovered that the export of these unclaimed skeletons was so lucrative that they turned to robbing graves in order to fulfill more orders. All of this was legal until 1985, when Indian authorities gained evidence that people were turning to murder in order to collect more bones, especially after officials found 1,500 child skeletons on their way out of India. Now smuggling bones out of India is illegal, but it still happens. Often. Up until 2001, a business in Kolkata named Young Brothers dealt in producing and trafficking skeletons, pulling in up to $15,000 every month. People eventually notified the police that the streets surrounding the storefront smelled like decay. When the business was raided, two rooms full of skeletons were found.2 Just a few years ago, in 2018, 50 human skeletons were found on a train heading to West Bengal. These skeletons travel to all parts of the world. In fact, a quick Google search leads me to multiple businesses in the United States and Canada where, if I wanted to, I could purchase a real human skeleton for about $5,500. One website whose business is based in California even sells a monthly subscription box of real bones. Many of these sites have disclaimers written across their home pages: It is completely legal to buy and sell human bones in the United States (except in Georgia, Tennessee, and Louisiana), and it is not legal to buy or sell bones of Native Americans, as those are protected by the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. Every single one of the websites I see claim to obtain their human skulls and skeletons in an ethical and legal way, but they provide no further information on how they go about doing that. A few clicks on Instagram lead me to people selling real human skulls and hands. I see a delicate skeletal hand holding a black flower under a glass dome for £900 and a store boasting that a new human skull has arrived in the shop. It honestly doesn’t seem that difficult to get my hands on real human bones if I wanted to.

But I don’t. I don’t at all. I understand the need for students to examine real specimens, and I also understand the natural curiosity that humans have with death. I know what it is like to look at human bones or a full-fledged skeleton and feel that shock of disbelief and recognition: this structure, bones just like these, are hidden from my view, but are within me at all times. Carrying me. Protecting my heart and liver and lungs. Of course we want to know what it is that holds us aloft above the earth. Of course we want to know what is inside us. It is, afterall, a strange sort of miracle.

But when I looked at the skeleton in my bio lab, I, of course, recognized the natural kinship I have with another human animal, but I also knew––deep, deep in my bones––that if I had not elected to donate my body to science, I would not want my bones to be in a cold classroom across the world.

Also in my biology class, my fellow students and I received the opportunity to go into the dissection room connected to our bio lab, where pre-medical students were dissecting two human cadavers who had been donated for this express purpose. The students painstakingly collected every piece of tissue and muscle and skin they cut away, storing everything in containers. At the end of the dissection, every single piece possible of these bodies would be returned to the families, who would then cremate the remains. We could not see the faces of the two bodies––they were covered for the privacy of the dead––but I could tell that they were elderly from the wrinkled skin peeking around the edges of the open cuts. And I knew that they wanted their bodies to be used in this way so that young scholars could learn from their remains on their journeys to helping others. When I stepped out of the dissection room, I saw the real skeleton hanging limp by the plastic replica across the room. Just moments before, I had been filled with fascination and a strange joy at seeing the inner workings of a human body, but as soon as I saw the skeleton, it was replaced by a hollow cold, an unsettled feeling deep inside that said: Something’s not right.

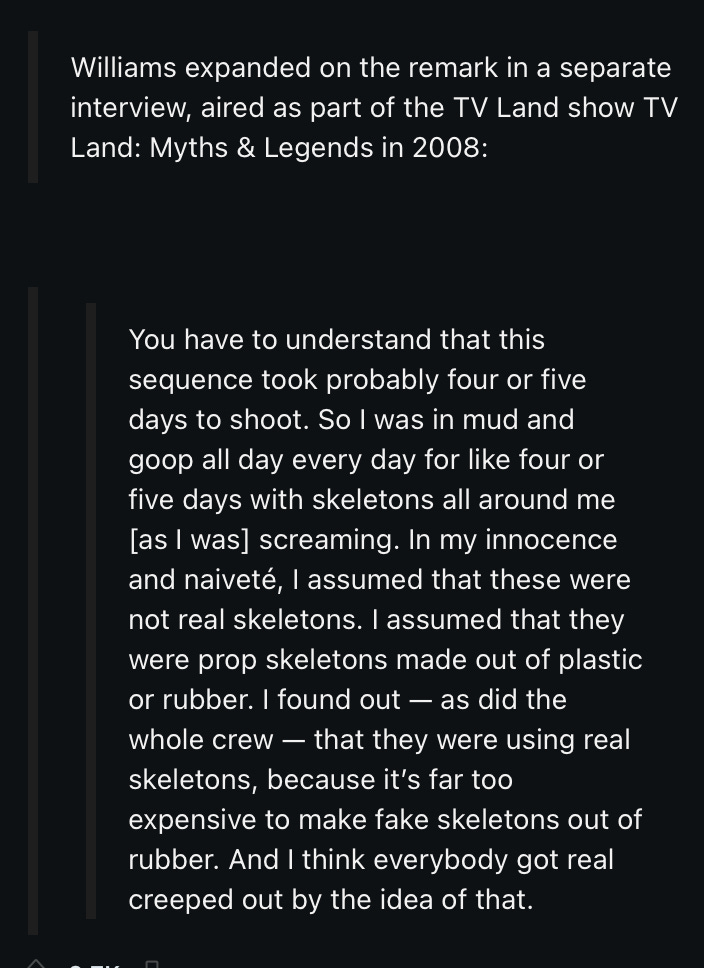

The truth of the matter is that the vast, vast majority of human skeletons we see in academic settings or in stores full of “oddities” or in museums are not donated by the dead themselves or their families. Many of them are picked up off the street, unidentified, or dug up from graves. They’re bought and sold by the living. They’re stolen. Then they’re used for learning or for decoration, or on the sets of movies––Poltergeist famously utilised real skeletons in filming because replicas were too expensive.

You might be thinking: But they’re dead. What do they care?

And you’re right. They’re dead. And it is the living who take great pains to care for the remains of their loved ones, visit their resting places, recall memories of those who have died. Plus, there’s no real way to return any of these remains to their homes or their families. It would be too costly to examine the DNA and there would be too many dead ends.

But I do think all of this is worth considering. How do we treat our own dead and how do we treat the dead family members of others? Does it matter what country they’re from? Does it matter if we’ve seen that country or know people from that country? And furthermore––who decides what makes an ethically obtained skeleton? The companies that profit off them? I would like to know what these middle-man business owners plan to do with their own bodies after they die. Surely, they must have thought about it, as they clicked on a new order in their inbox, as they printed a shipping label, as they handled and packed the bones of a human who was once alive. Or maybe they haven’t. Maybe they’re not as curious about the bones in front of them as I would be. Maybe I’m sentimental. Too sensitive. I mean, they’re just bones, right? Once we’re gone, we’re gone.

But we’re also not. No matter what happens to our souls or spirits or inner selves when we die, our physical matter is left here on Earth. I have never balked at the thought of people turning cremains into jewelry or donating bodies to science or shooting their remains into space or planting them beneath growing trees. None of that gives me pause, because the dead person or their family got to choose what happened. I think all of us deserve a choice.

I haven’t seen the skeleton at my college in almost a decade, but I think of her fairly often. I have long since forgotten all of the names of the bones in the human skeleton. That is not the lesson I took with me after passing my biology class. Instead, I was left with an almost existential bereftness: I held within me fascination and wonder at the human body as a result of my education, but I also felt a sad helplessness at the colonialist and capitalist principles within which academia acted, in this case in the buying and selling of or accepting donations of “ethically” obtained human skeletons from other nations. Considering the skeleton and her past opened up new avenues of thought and curiosity for me. But at what cost?

When I think of the skeleton in my biology class, I worry that she’s lonely, or that her spirit or soul is unhappy with where her physical body has ended up. Living bodies crowd around her for a few hours a day and then they’re gone. She’s left beside a plastic skeleton, behind glass windows that look out onto manicured grass and kids with backpacks full of books. Students will graduate, a new crop of young biologists will enter the room, and still, she’ll be there, hanging. I don’t know her name. I don’t know for sure where she is from. I don’t know if she would have wanted to be learned from in her death or if she doesn’t care at all. I don’t know, really, anything about her. But I do know that she was once alive.

Ray, Sanjana. “Decoding India’s Secret Trade of Bone Smuggling.” The Quint. 5 December 2018.

Carney, Scott. “Inside India’s Underground Trade in Human Remains.” Wired. 27 November 2007.

Or sits*

I really loved this well thought out and deep essay. I recently wrote about skeletons and skulls in one of my own posts. I think about my own skeleton often and my mind often wonders on the medical field and skulls and bones both assembled by hands, and dismantled by the elements and time. As well as in academia settings. It feels as though it would be a form of enslavement after death to be permanently stationed in a stuffy classroom with only the most boring texts, never getting to learn something new because you hear the same lectures year after year. Time after time, you meet some one new in their alive form. They only think about base desires. Or how they hope they pass their courses but they have a hang over. Nothing of the stars or poetry. I wonder how often a person such as yourself thinks about her. Sit with her in silence, hoping she's reached a new horizon after death. May she be resting in peace, and not stuck in an eternal anxiety dream where she forgot her skin. I wanted to let you know this post inspired me in profound ways. Thank you